Geoffrey Hinton, the “Godfather of AI,” recently remarked that “machines could take over” because they have the ability to learn independently and share their knowledge.

He then went on to say that it’s conceivable that AI could “wipe out humanity.”

The fact that artificial intelligence is rapidly altering human society makes Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein particularly relevant.

See my memorandum Artificial Intelligence and Human Fears.

In Colossus: The Forbin Project, Dr. Charles Forbin (Eric Braeden) builds Colossus, but despite its’ superior intelligence, he still expects his creation to be subservient to him, and to human instruction.

Colossus (at this stage, at least) does wish to preserve humanity as a whole.

However, it also believes that by being a dictator over humankind, it can do a better job than any humans could, and is willing to sacrifice human lives along the way.

In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Victor Frankenstein creates a being who is better able to learn, and also physically more powerful, than himself.

In all aspects, except attractiveness, it seems to be superior in many ways.

He’s unable to be a good father to this creature, however, and the creature murders all the beings who Victor Frankenstein loves.

When Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley began her first novel Frankenstein (1818), she was 18 years old.

Despite her age, she created a work—arguably the first true science fiction novel—that still inspires other artists today.

While Mary Shelley didn’t believe in organized religion, she did believe in the existence of God.

In Frankenstein, this teenager explored themes of good and evil; prejudice; loneliness; human control; and the limits of scientific knowledge.

Mary Shelley was the daughter of the famous feminist Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women, but her mother died a few days after giving Mary birth.

Her father, William Godwin, was an influential journalist, philosopher, and publisher, who wrote An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice.

Alienation must have been an easy subject for Mary to write about.

She had a fraught relationship with her stepmother.

She was shunned by society after she escaped from her father’s influence with a married man, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Only one, of her four children with Percy Shelley, survived to adulthood.

She and the great poet, Shelley, eventually wed.

However, she became a widow when she was 25.

Mary Shelley died at the age of 53, of a brain tumor.

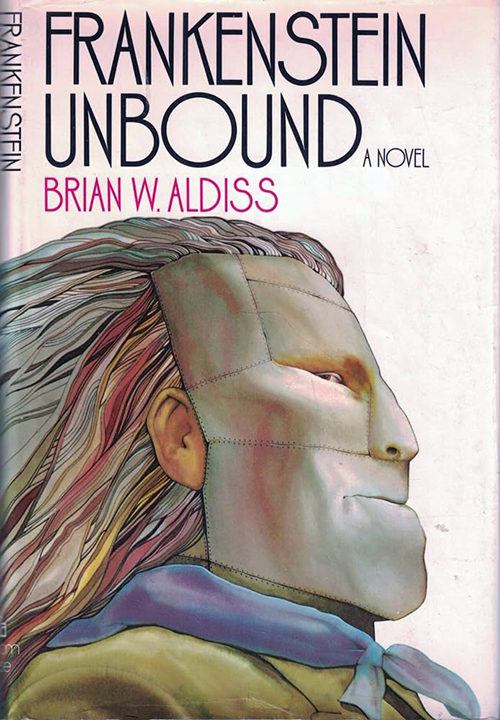

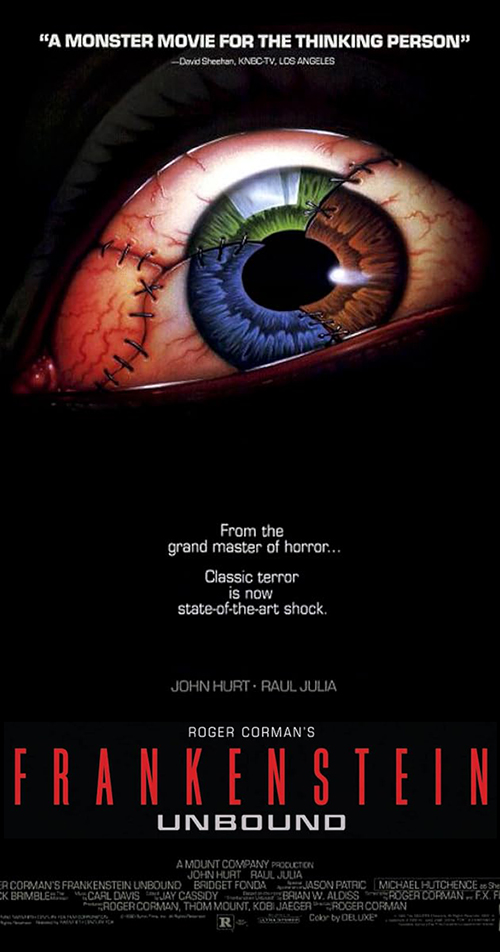

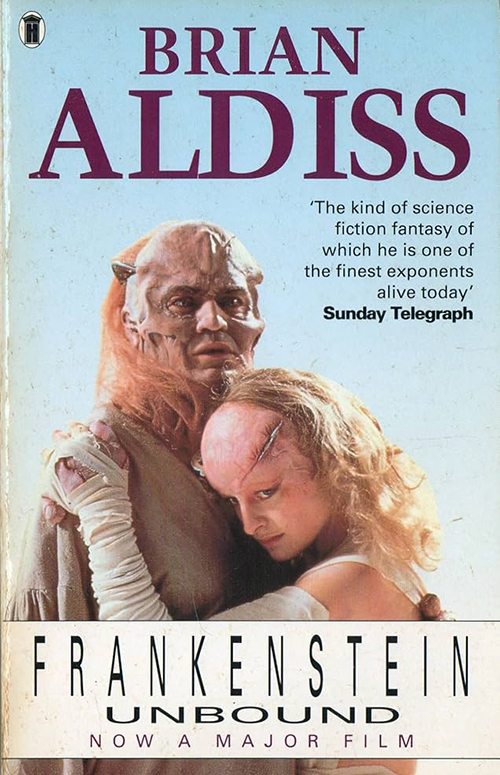

One idea that Mary Shelley’s novel, Whale’s two films—Frankenstein (1931) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935)—and the Corman film Frankenstein Unbound (1990), have in common is that the monster is not a true monster at all.

He’s a lost desperate soul, who turns to vengeance and murder, after his needs are met with cruelty.

Can such a creature have a soul?

In the 1818 book, the monster kills at least four people.

He kills Victor’s young brother William, and frames William’s nanny Justine for the crime.

Later, he rapes and murders Victor Frankenstein’s fiancé Elizabeth on Victor’s wedding night.

Finally, he murders good Henry Clerval, Victor’s friend since childhood.

However, he comes to love the DeLacey family, especially the old grandfather.

By the end of the book, the creature is filled with remorse for his crimes, and wanders off, to commit suicide.

Although the “creature” in the 1818 novel, is much more articulate than the “monster” in the 1931 and 1935 films, there are key scenes in the films that reveal his capacity for goodness: the scene with the little girl by the lake, and the scenes with the blind hermit (a similar character to the DeLacey grandfather).

Both scenes are given power by the magnificent performances of Boris Karloff.

However, the monster does murder the little girl (perhaps because he believes she can float); does throw “his Master” off the old windmill in the 1931 film; and kills or injures people in both films.

At the end of Bride of Frankenstein, the monster is filled with self-loathing.

He tries to commit suicide, and allows Victor and Elizabeth to escape the lab.

Note: When Frankenstein was reissued in 1938, the scene with the little girl was cut.

The footage was lost until 1985, when the scene was partially restored.

In Corman’s Frankenstein Unbound, the monster murders Victor’s fiancé Elizabeth, Frankenstein himself, and several villagers.

Unlike other versions, this monster doesn’t commit suicide, but is killed by scientist Dr. Joe Buchanan for being an aberration, not created by God.

By the end of the film, Buchanan identifies completely with Victor Frankenstein.

In Corman’s Frankenstein Unbound, the creature interrogates Dr. Joe Buchanan as to when Victor Frankenstein created Buchanan.

He’s surprised to learn that Joe thinks himself created by a being called “God.”

Corman’s monster is intellectually between the articulate being in the Shelley novel, and the grunting child-like creature in Whalen’s Bride of Frankenstein.

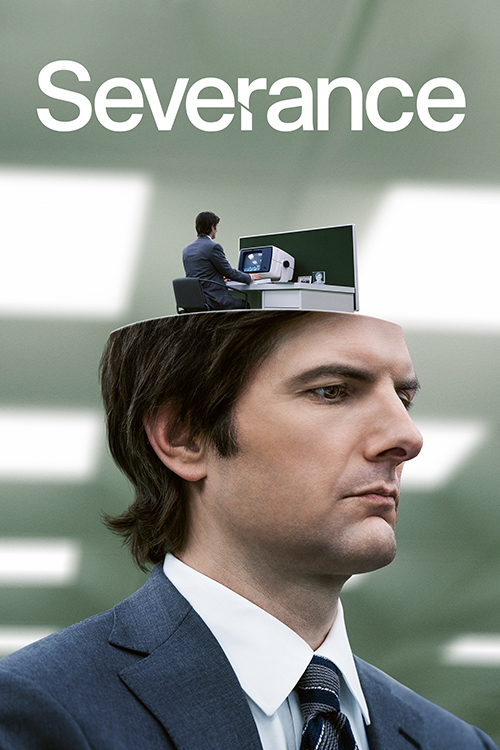

Humans are using human-created artwork, and our written work, to educate AI, and make AI more intelligent than we are.

Victor Frankenstein used odd parts from graveyards to build his creature, and this resulted (in Mary Shelley’s words) in a “thing such as even Dante could not have conceived.”

The data in ChatGPT comes from wild sources like forums, Twitter, Wikipedia, and Facebook, as well as from edited books.

These sources contain conflicting information!

No wonder, ChatGPT sometimes goes mad and spins tales about fake people, and events!

How can software like ChatGPT believe in an absolute truth?

Midjourney images are “built” from billions of images stolen from the open web.

Much of the “raw material” is not keyworded* correctly.

That’s why a video of New York was used to represent London crime in an TV ad for mayor of London (2024).

That’s why a video of a Ukrainian man was used to represent a basement-dwelling American, in a 2023 Republican commercial blaming President Biden for inflation.

Many stock images, and videos on the world market, are generated by Russian, Ukrainian, and Estonian photographers.

It’s an easy way for creatives to obtain another “revenue stream.”

Ridley Scott’s film Alien: Covenant (2017) is a modern retelling of Frankenstein, with Walter as the “good side” of the monster, and David as the “evil side.”

In the prologue, Peter Weyland explains to David that “one day they will search for mankind’s creator together.”

Years after Weyland has died, David drops a bio-weapon on the planet of the Engineers (a giant alien race that facilitated the evolution of humans), thereby punishing the creators of his creator.

In the original Frankenstein novel, Victor (traumatized by his mother’s death) develops a method to give life to non-living matter.

This experimental creature kills all the people who he loves.

In Corman’s Frankenstein Unbound, Dr. Joe Buchanan believes he can create a super weapon that will end all wars.

Instead, he creates timeslips and ends human civilization.

In Ridley Scott’s Alien: Covenant, Peter Weyland creates a synthetic in the image of Michelangelo’s David.

The superior android David is scornful of his weak, human master.

Yet, later he feels a type of love for scientist Elizabeth Shaw (2012’s Prometheus).

Nevertheless, he plots vengeance on the alien race (the Engineers), as well as all the life forms that they “helped along.”

Today, scientists like Dr. Frances S. Collins (former leader of the Human Genome Project) and computer scientist Geoffrey Hinton all believe that science can help humankind make great advances.

At the same time, both warn that there are ethical issues to consider.

Yes. Knowledge can lead to progress, but scientists must tread carefully.

A false step can lead to the end of humankind.

*The rights to photographs and videos sold by commercial agencies (like istock, Shutterstock, and Getty), are routinely associated with “keywords,” so that these images may be used accurately. Sometimes, the keywords are not correct.