Based on the book series by Isaac Asimov, Foundation is about a mathematician named Hari Seldon, who becomes the first psychohistorian.

He predicts that the Empire is approaching its’ decline and fall.

However, between his time, and the far future, there will be several crises (or tipping points), during which the coming period of disorder may be shortened with his assistance.

Seldon sets out to establish a society, a “Foundation,” to cope with these crises, and save human civilization from barbarism

The U.S. has had its’ own “tipping points.

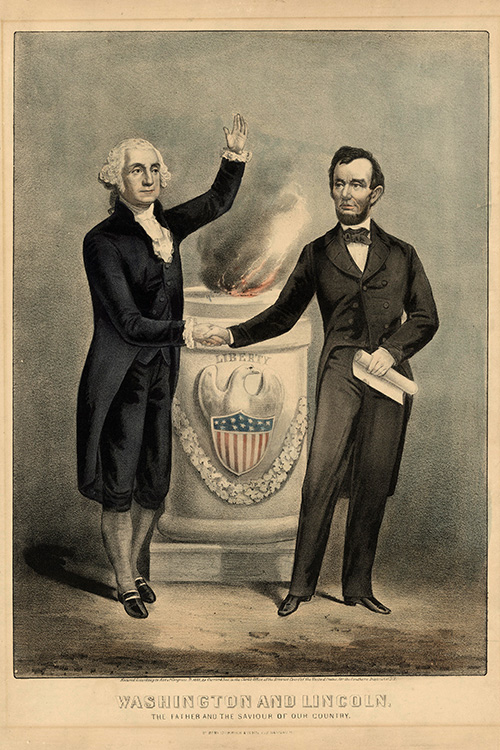

The first was the country’s birth.

In 1776, many colonial citizens were too conservative to rebel.

Thousands of Loyalist families fled to Britain, or Canada, leaving their wealth behind.

Perhaps, if all white men over the age of 16 had voted “Yay” or “Nay,” the colonies wouldn’t have separated.

According to Wealth and Democracy, by Kevin Phillips: “Only supporters of Independence were allowed to vote [for the Declaration of Independence], Tories being barred, and with prewar property requirements also set aside.”

The Founders needed “the rabble” to set up a new country.

However, many of the Founding Fathers could only imagine a hierarchy of Anglo-Saxons being in control.

Another “tipping point” occurred in 1861 when eleven Southern states declared themselves a separate country.

However, the real crisis had begun years before the South seceded, with a general lack of respect toward the Federal Government that grew with each inadequate presidency.

Southern newspapers convinced their citizenry that if Abraham Lincoln were elected, he’d arm slave revolts, give their daughters to Black men, and make the South destitute.

It had become illegal to even discuss abolition publicly in most Southern states, and over twenty Northern abolitionists were lynched.

(The Unpopular Mr. Lincoln, by Larry Tagg.)

The U.S. was forced to choose between a weak central government (and the enslavement of almost four million Black people), and remaining the united country that the Founding Fathers had dreamed of.

In 2004’s C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America—a satirical “documentary” in which the South won the Civil War, written and directed by Kevin Wilmott—Wilmott shows the C.S.A. becoming an Empire, and taking over sections of Central and South America in order to keep the slave system going.

Those scenes seemed hyperbolic until I learned the story of William Walker.

Walker was a young Southern doctor who in 1856 traveled to Central America and made himself the President of Nicaragua, (thus creating a slave country south of the border).

U.S. President Pierce actually recognized Dr. Walker’s government as legitimate!

Walker’s regime lasted less than a year.

A few years later, he tried for power once more (this time in Honduras), was captured by the Brits, found guilty in a court, and executed by firing squad.

The 1930’s were another tipping point, when the Great Depression resulted in Democracies ending all over the world, and international trade breaking down.

(The fact that this was a reactionary period, wasn’t covered well in my high school history book.

If Franklin Delano Roosevelt—the President from 1933 until his death in 1945—hadn’t used his power judiciously, or if the U.S. hadn’t become united by World War II, perhaps we wouldn’t live in a Democracy today.

Yet another tipping point occurred in 2020, when publicity-seeker Donald Trump—less a populist than a Hero of Hierarchy—lost his opportunity to serve a second term.

This continuing crisis is more like the 1930’s tipping point, then the ones in either 1776 or 1861.

Although a few U.S. representatives propose that the U.S. split up into red and blue states, that wouldn’t work today.

(Too many states are purple.)

Just as 1930’s isolationists flirted with Fascism, Trump created MAGA by convincing Americans that he had the ability to wall them off from “out groups,” as well as put a halt to societal change.

Close presidential races have occurred before.

However, those elections weren’t “tipping points.”

Four presidents were assassinated—in 1865, 1881, 1901, and 1963—but those tragedies didn’t create chaos.

Most folks viewed the two parties as too similar to really care who won.

In too many elections less than half of Americans vote.

No one state, or group of states, got everything they desired in the U.S. Constitution (written in 1787), but that was the point.

People got together and bargained, and the majority opinion won.

The Constitution, and Bill of Rights, were written to work hand in hand with a Democratic society, and Democracies work best if people are free to do whatever, as long as doing so doesn’t harm others.

As the saying (attributed to multiple people) goes: “Your right to swing your arms ends just where the other man’s nose begins.”

The framers erred in hoping that slavery would gradually fade away.

They also made a mistake in creating the Three-fifths Compromise,* enticing Southern states to sign the Constitution by trading this compromise for a bit more power.

(This strange agreement “baked” the concept of slavery into the Constitution.)

Eventually, wealthy Southerners conflated their own freedom with the freedom to be “on top” of the societal heap, and to own other people.

One way of thinking about each U.S. crisis is that they centered around reactionary cycles and hierarchy.

However, as Lincoln (the disciple of Washington) expressed it in his Gettysburg Address, the U.S. needs a Federal Government that is: “Of the people, by the people, for the people.”

There’s simply no room for hierarchy in that phrase.

In the crises of 1861, 1933, and 2020, large segments of American society feared that their ways of life were being threatened.

They became resentful of other Americans, and valued “Anglo-Saxon order,” and wealth, over the Democratic system.

Hierarchy, and not caring about the general good, is a very bad fit with Democracy.

We are now at a crisis point.

* The Three-fifths Compromise was an agreement—in the U.S. Constitution—that included slaves in the state populations, but in a very peculiar manner. It specified that each slave would be counted as 3/5th of a human being. The resulting totals were used to calculate the number of seats in the House of Representatives, the number of electoral college votes, and how much states would pay in taxes. Although slaves couldn’t vote, slave-holding states ended up with more state representatives, and more electoral college votes, than they truly deserved.