Only those born before 1980 are considered digital natives.

I’m classified as a digital immigrant, because I was born around the same year as the Ferrante Mark I—the world’s first general-purpose computer.

I grew up in the days of rotary phones and three TV networks, and I didn’t own a personal computer until the early 1990’s, when I purchased my first OS6 Macintosh.

I went through a phase when I played games on my Mac, but I only liked clue-finding games.

I never devised an avatar, or played computer games with people around the world.

I met my husband at an office for freelancers—where people could get their resumes typed and use drop off boxes—not via Hinge or Tinder.

My only avatars are the sticker emojis I made on my iphone, and the self-portrait I cobbled together from ready-made choices for Facebook.

My favorite Apps are IMDb, the FoodNetwork, YouTube, and Goodreads—sites where I can look up information or be entertained, not communicate with others.

I’m definitely a digital immigrant.

Most of the science-fiction I read is old—very old.

I enjoy rereading authors that I first read in the 1970’s—among them, Isaac Asimov, Primo Levi and Olaf Stapledon.

Authors have been discussing the ideas of whether artificial beings should be legal “persons,” or whether artificial intelligence will supersede humans, for a very long time.

In order to broaden my horizons, I decided to read more recent science-fiction, and I happened upon The Lifecycle of Software Objects by Ted Chiang.

According to Wikipedia, Chiang isn’t a digital native either.

(He was born in 1967.)

However, he’s won four Nebula Awards and four Hugo Awards; and he writes philosophical science-fiction—my favorite category.

Just as Karel Capek invented the word “robot” for his 1921 play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), Chiang invented the term “digient” for “digital entities.”

In The Lifecycle of Software Objects, digients are virtual pets created as past-times for wealthy customers, who are then expected to parent them.

The novella is the story of two central characters (Ana and Derek), and their digients (Jax, and siblings Marco and Polo).

At the beginning of the story, Ana and Derek both work for a company that creates and sells digients.

After the software company goes bankrupt, Ana and Derek opt to take over the care of their favorite digital entities, so that their cherished entities may “live.”

Chiang deals with both psychological and philosophical issues in The Lifecycle of Software Objects.

The principal subject is raising and educating the “infant” digients.

He further mentions that digients are equipped with “pain circuit breakers,” so they’ll be “immune to torture,” and thus “unappealing to sadists,” bringing up the fact that sociopaths will still be a societal problem in the near future.

I especially enjoyed the message board sequences in which obviously “bad” parents grouse about their “bad” digient children.

At one point in the story, the digient siblings, Marco and Polo, ask to be “rolled back” to an earlier point in their “lives,” because they’re unable to resolve an argument.

Is it right for “daddy” Derek to allow this; or should he force his “children” to work out their own disagreements, so that they may grow emotionally?

Later, Marco and Polo ask to become corporations, or legal persons.

Should Derek permit this?

Is it child abuse to separate a digient from its’ friends, and fan clubs, or to alter its’ programming so that it can become a sex slave?

In Chiang’s novella, Ana disagrees with a company that wants her to help train a digient that “responds like a person, but isn’t owed the same obligations as a person.” [Italics mine.]

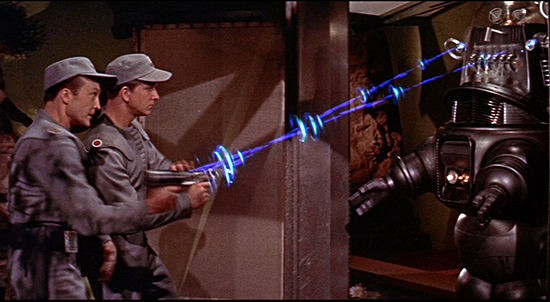

This scene reminded me of two TV series in which androids/robots are traumatized—The Orville (2017-?) and Westworld (2016-2022).

In season two of The Orville, we learn about the history of the Kaylons—a society of sentient artificial lifeforms (created as slaves) who exterminated the biologicals who created them.

In Westworld, the first season begins with human-like androids being the prey of depraved humans, but by season four it’s all-out war between androids and humans—that seems to end on earth in the same result as on planet Kaylon.

The central question is whether it’s ethical to enslave a sentient being—be it a virtual entity, robot, android, or human.

Is enslaving non-biologicals just as wrong as enslaving a fellow biological?

In a world in which human life is less important than money, is it senseless to worry about the treatment of virtual or robotic creatures?

After all, while many of us say we believe in fair play, unselfishness, and truthfulness; almost no one thinks we should carry through with these beliefs in our daily lives.

People can justify any bad action, as long as it makes them feel better.

We can justify not paying back a loan because the lender has more money in the bank than the lendee.

We can justify breaking laws, because other people are more corrupt—the classic pot calling the kettle black.

Few believe that the way to build a life is to be honest and truthful all the time.

Some of my favorite novels on this subject are not science-fiction.

(I recommend two Fyodor Dostoevsky novels—The Idiot, and Demons, also titled The Possessed.)

Because people can justify any bad action, the erosion of generally-believed truths is quite dangerous for society.

A 2016 Sanford study* came to the conclusion that digital natives are unable to judge the credibility of online information, or distinguish between an advertisement and a news story.

The inability to tell truth from truthiness (on the web) is also evident in digital immigrants—perhaps, more so.

In a world where we have no generally believed truths, and we only believe what we want to believe, how is an organized society possible?

We first heard the word “truthiness” on The Colbert Report—Stephen Colbert’s mock news show (which aired from 2005 through 2014), in which he portrayed a far right news personality.

In Colbert’s book America Again (2012), the same character satirically discusses voter fraud (page 165) and goes on to recommend ending voter fraud by ending voter registration (page 166).

Little did anyone think in 2012, that 10 years later, in 2022—40% of us would believe that the 2020 election was illegitimate, or that later several states would actually pass laws making it harder to vote.

Ultimately, the most important conflict is not one between digital natives and digital immigrants, right versus left, the intelligentsia versus average people, or even “woke” versus “anti-woke.”

Instead, I think that the most crucial divide is between people who want to try and seek out truth and reality in this confusing world, and those who prefer living in their cocoons.

*”Evaluating Information: The Cornerstone of Civic Online Reasoning,” by Sam Wineburg, Sarah McGrew, Joel Breakstone and Teresa Ortega (2016) the Stanford History Education Group.