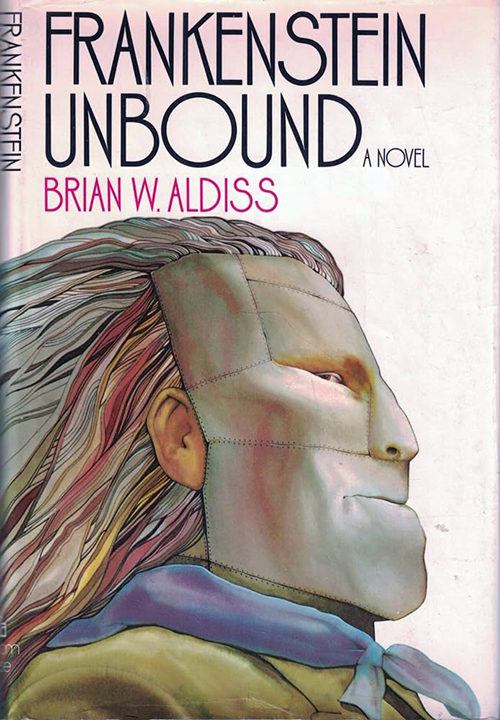

Author and Anthology Editor Brian W. Aldiss, as well as his companion novels—Frankenstein Unbound (1973) and Dracula Unbound (1990)—were well known during the late 80’s/early 90’s.

Both featured a main character named Joe Bodenland.

Frankenstein Unbound was about a fired U.S. Presidential advisor who travels in time (from 2031 to 1817) where he meets a mad Dr. Victor Frankenstein, as well as the author of the fictional work herself, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley.

In the first chapter of the Aldiss non-fiction work Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction (1973), he made the controversial proposal that Mary Shelley wrote the first true science fiction novel when she wrote Frankenstein.

He also gives his proposed definition of science fiction:

Science fiction is the search for a definition of man and his status in the universe which will stand in our advanced but confused state of knowledge (science), and is characteristically cast in the Gothic or post-Gothic mold.*

In 1990, Roger Corman chose Frankenstein Unbound for his first directing challenge, after a 15-year gap.

This memorandum is a comparison of the two works.

Part Two will be a memorandum on the themes of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and how her ideas about science and religion were transformed, and used, in the various films about her characters.

One difference between the Aldiss novel, and the Corman film, is the profession of the main character.

In the novel, the hero is a failed Texan politician named Joe Bodenland.

(He’s a married man—licking his political wounds after being fired—while his wife is away from New Houston on a business trip.)

In the film, Joe is a brash scientist who’s designed a super weapon more destructive than the atomic bomb.

At the beginning of the film, Dr. Buchanan is conducting an experiment.

His team blows up a small version of the Statue of Liberty in front of an audience of dignitaries.

Although there are shields protecting them, most viewers end up covered with ash, and with disheveled clothing.

The year is 2031, and Dr. Buchanan is a scientist seeking more funding for his project.

I’m not sure why Buchanan is destroying this particular statue, and it’s not a particularly strong beginning for the film.

For the rest of this memorandum, I’ll refer to the hero in the book as “Texan Joe B” and the film hero as “Dr. Joe B.”

“Joe” will refer to both characters.

The main point of both stories is that not all scientific knowledge leads to progress.

There’s a big side effect to Dr. Joe B’s weapon.

It has accidentally created “timeslips,” events in which random people travel in and out from the present to the past.

In the novel, Texan Joe B hasn’t caused “timeslips;” in the movie, Dr. Joe B has.

In both versions of Frankenstein Unbound, Joe is zapped (along with his automobile) via a timeslip, from the mid 21st century back to 1817 Geneva, Switzerland.

(Luckily, Texan Joe B speaks fluent German.)

In Geneva, Joe meets Dr. Victor Frankenstein, his monster, his fiancé (Elizabeth), Mary Shelley, as well as poets Lord Bryon, and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

In the movie, Dr. Joe B runs into trouble when he tries to prevent Justine Moritz (a young woman falsely accused of murdering Frankenstein’s nephew) from being hanged.

In the novel, Texan Joe B is tossed into jail, accused of murdering Dr. Frankenstein himself.

In the film, the scientist’s talking car has a nuclear-powered engine, and it’s able to drive itself.

In the novel, the politician’s car doesn’t talk, is electric, and is outfitted with a swivel gun on the roof.

(The talking car in the movie is played by a 1988 Italdesign Aztec concept car.)

In the film version of Frankenstein Unbound, Frankenstein constructs the female monster with the head of Victor’s fiancé Elizabeth, and the female monster has a slight, delicate body.

In the novel, Frankenstein constructs the female monster with the head of the hanged servant girl (Justine), and the body of the female monster is just as large and ungainly as that of the male Frankenstein monster.

If the screenwriters for the film version of Frankenstein Unbound (Roger Corman and F.X. Feeney) had included more of the Aldiss novel in the script, it would have been an R-rated, or even an X-rated movie!

Mary Shelley is a very sexual woman in the book. She goes skinny dipping with Dr. Joe B, and breastfeeds her infant son William as they talk.

Moreover, Aldiss goes into graphic detail about drawings of the sexual parts of the “monsters” in Dr. Frankenstein’s lab.

(This scene in the Aldiss book, reminded me of android David’s lab in Ridley Scott’s 2017 film Alien: Covenant.)

Rather than spend money on Frankenstein’s lab, however, Roger Corman chose to spend his budget on ripped-apart sheep, the Frankenstein monster assaulting villagers, and the death scene of the monster at the end of the story.

Unfortunately, most of the practical special effects—with the exception of the monster death scene—weren’t well executed.

In the novel, Texan Joe B watches as the two monsters mate for the first time.

(He had intended to kill them, but instead watches as they have sex.)

The only sex scene in the film is between Dr. Joe B (John Hurt) and Mary (Bridget Fonda).

However, the scene is more suggestive, than graphic.

(I’ve always loved John Hurt, so it’s nice to see him as a romantic lead.)

In the novel, we hear a lot more from Lord Bryon, Mary Shelley, and Percy Shelley, than in the film.

In place of philosophical discussions about human society, the movie audience is given human arms torn out of sockets and gutted sheep that appear to be breathing.

At one point in the Aldiss novel, Lord Bryon says:

“Is it possible that machinery will banish oppression?” he asked. “The question is whether machines strengthen the good or the evil in human nature, So far the evidence is not encouraging, and I suspect that new knowledge may lead to new oppression.”

In both versions of Frankenstein Unbound, the Joe character loses his moral compass and becomes prey to wild dreams.

By the end of the novel, Texan Joe B kills three of the novel’s main characters: Victor Frankenstein, the monster’s mate, and finally the monster himself.

At the end of the movie, Dr. Joe B does kill the monster, but it’s partially in self-defense.

It’s Dr. Victor Frankenstein who killed the female monster, and the monster who killed Victor.

At the end of both works, Joe trudges off into the snow.

*In his essay “A Monster for All Seasons” (in Science Fiction Dialogues, 1982) Aldiss says that “mode,” might have been a better word than “mold.” Also, (says Aldiss) perhaps he should have left out the phrase “Gothic and post-Gothic.”

No comments:

Post a Comment