In her book, The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity, Jill Lepore explains the roots and aftermath of King Philip’s War (1675-1676) in which thousands of Native Americans, and Puritans, died—men, women, and children.

In the aftermath part, she explains how famous American actor, Edwin Forrest, won great success (in 1829) with a play he had commissioned: Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags.

The play, Metamora, is the story of a noble Native American chief driven to war by English treachery.

Rapturous audiences applauded the defiant words of a long-dead First American.

Oddly enough, this play was performed during the same era when President Andrew Jackson put through the Indian Removal Act of 1830!

(This notorious Act forced more than 60,000 people to be moved to the other side of the Mississippi River, in a “Trail of Tears.”

(Thousands of Native Americans died along the way, or soon after arriving in Kansas and Oklahoma.)

In Act Two of the play, Metamora proclaims:

White man, beware! The mighty spirit of the Wampanoag race are hovering o’er our heads; they stretch out their shadowy arms to me and ask for vengeance; they shall have it. . . From the east to the west, in the north and in the south shall cry of vengeance burst, till the lands you have stolen groan under your feet no more!

What is it that made English-Americans applaud as a white actor bellowed out these words?

What is it, that made Americans alternately praise the beauty and power of Native American cultures, and then commit genocide against them?

That’s the issue that Jill Lepore deals with.

Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags was loosely based on the life of King Philip (1638-1676, also known as Metacomet/Metacom), chief of the Wampanoags.

(The Wampanoags, or People of the First Light, lived in Cape Cod, and the islands of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard.)

Philip was the second son of Ousamequin/Massasoit—the same chief/sachem who saved the Pilgrims in the first Thanksgiving (1621)—and he succeeded his father in 1662, after his elder brother died.

By the end of the war (as discussed in The Name of War), half of New England towns were reduced to ashes.

Many Christian indigenous people (who had assimilated and were living on their farms) were transported to island prison camps, left to starve and to die.

After King Philip was killed—and his head hung in the center of Plymouth, Massachusetts—the brief war ended.

Hundreds of indigenous noncombatants were sent into slavery—to the West Indies, and possibly North Africa—alongside the wives and children of known combatants.

(The slave money—from selling Native Americans—helped rebuild after the war.)

King Philip was blamed for uniting with the Narragansett tribes, and for starting the war.

Purportedly, the war began after three Wampanoag men were tried, and hanged, for killing John Sassamon—a Christian, Harvard-educated indigenous man—who was both a schoolmaster and a minister.

(Supposedly, King Philip was angry because Sassamon had informed the English that Philip was planning a war.)

Native American leaders, however, were becoming very tired of Englishmen both taking their lands, and trying to convert them to the British way of life.

The Wampanoags and the Narragansetts attacked various New England towns, and (after more than a half century of peace) the Puritans had a full-scale war on their hands.

A major point in The Name of War is that the war came at a time when Puritan religious leaders were concerned that living close to indigenous peoples was making white Americans “less civilized” and “less English.”

Lepore notes:

Building a “city on a hill” in the American wilderness provides a powerful religious rationale, but on certain days. . .it must have fallen short of making perfect sense. When the corn wouldn’t grow, when the weather turned wild, these are the times when the colonists might have wondered, What are we doing here? . . . as many as one in six sailed home to England in the 1630s and 1640s, eager to return to a world they knew and understood.

While some religious leaders—like Baptist Roger Williams and Puritan John Eliot (creator of the “Indian Bible”)—were intent on Native Americans converting and assimilating, other leaders wanted the First Americans to live in separate villages, if they lived at all.

At the same time, many leaders like King Philip never became Christians, and decided that the only path to keeping their freedom, was to fight back.

The TV series Daniel Boone starred Fess Parker in the title role, and aired from 1964-1970.

(Daniel Boone lived from 1734 until 1820, and so he lived about 100 years after King Phillip.)

Non-indigenous Ed Ames played Boone’s Oxford-educated, half-Cherokee friend, Mingo, for 72 out of the 165 one-hour episodes.

Ed Ames’ parents were immigrants from what is now Ukraine.

Mingo was not a real historical figure.

However, he reminds me somewhat of John Sassamon (mentioned above)—a Harvard-educated Algonquian, raised to be Christian by his Native American parents.

John Sassamon, like Mingo, lived on both sides of the cultural divide.

“Mingo” was short for “Caramingo,” and his English father was the fourth Earl of Dunmore.

From the Native American perspective, “mingo” is a word for “chief” in the Choctaw language.

Besides John Sassamon, Mingo’s character also resembles Joseph Brant—a Mohawk, who was a captain in the British Army—and was educated at Moore’s Indian Charity School (the precursor to Dartmouth College).

Other members of the large Daniel Boone cast were “Rosey” Roosevelt Grier and Jimmy Dean.

Former football star “Rosey” Grier played escaped slave, Gabe Cooper, for 16 episodes.

Singer and actor, Jimmy Dean, (whose voice we hear in sausage commercials) played three different frontiersmen (including Jeremiah) in 15 episodes.

Reviewers have criticized the series for not being historically accurate, pointing out that Boone never wore a coonskin hat.

(The real Boone preferred more-elegant felt hats to hunting hats.)

Mingo is accused of crimes in Daniel Boone TV episodes like “My Brother’s Keeper” (season 1, episode 3), and “A Rope for Mingo,” (season 2, episode 11).

However, the story drawn in the comic book “The Murderers’ Cave” never aired.

In this story, Mingo is accused of murder by two disreputable white men, but their word is believed over Mingo’s, because he’s only a savage.

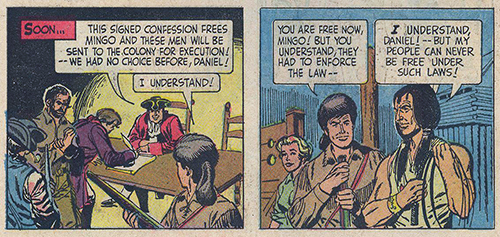

By the end of the trial, Daniel Boone says; “You are free now, Mingo! But you understand, they have to enforce the law . . .” and Mingo responds: “I understand, Daniel . . . but my people can never be free under such laws!”

(Was the dialogue “too liberal” for the times?

Is that why this particular script never aired?)

Nearly 350 years later, we (in the U.S.) are in a similar position to the New England indigenous tribes versus the New England Puritans during King Philip’s War.

On one side, about half of us want to live in a melting pot—with all of us having our different religions, and our different identities—but trying not to step on one another’s toes.

On the other hand, about half of us want to be “Englishmen,” with an out of proportion attachment to material possessions.*

*Jill Lepore notes, in The Name of War, that Native Americans rejected “the English conflation of property and identity, saying: We have nothing but our lives to loose [lose] but thou hast many fair houses cattell [cattle] & much good things.” (Italics and bold face mine.)

No comments:

Post a Comment