Poster from Gabriel Over the White House, starring Walter Huston, as President Hammond.

There’s a lot about U.S. history that I didn’t learn in school.

For example, I learned this year that Republicans took the presidency from a Democrat before 2000.

(The “election” was in 1877, a backroom deal—in which 20 electoral votes were conceded to Rutherford B. Hayes, to end Reconstruction—which made Hayes the 19th President by a single vote!)

In addition, I wasn’t aware that, during the 1930’s, America teetered on the edge of giving up on Democracy.

Evidence for a “lack of confidence” in Democracy can be found in the 1933 film, Gabriel Over the White House—directed by Gregory La Cava, and financed by William Randolph Hearst.

(Hearst was a newspaper publisher and politician; his life was one of the inspirations for Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane.)

“Gabriel” is the story of a political hack who’s elected President.

Early in his presidency, he nearly dies after speeding.

After the car crash, he changes from a figurehead, to an activist intent on saving the country.

According to IMDb, the film was released with two different endings—an American version and a little-seen European version.

(I’ve only seen the American version. According to sources on IMDb, the European ending is similar to that of the original novel. See below.)

When President Hammond (Walter Huston) is elected, he’s a caricature of a glad-handing politician.

He jokes about not fulfilling election promises.

His knowledge of geography is nil, so he asks his attractive young secretary (with whom he’s having an affair) where Siam is.

He’d rather crawl around on The Oval Office floor—with his four-year-old nephew—than pay attention to an army of the unemployed marching on Washington.

After Hammond awakens from his coma, however, he refuses Cabinet pleas to “defend the Capitol.”

Instead, he supplies food to the homeless men, and promises them jobs.

Dramatic lighting (and the sound of faint trumpets) reveal that this is a new President, guided not by his party’s needs, but by the Angel Gabriel.

The film script was based on a science fiction fantasy entitled Rinehard, by British author Thomas F. Tweed.

In the novel, American President Rinehard, changes, after a car accident, from a fan of “detective and wild west” tales, to a reader of political and economic tomes.

He dissolves Congress, fires his cronies in the Cabinet, declares martial law, creates his own militia, sets up agents in all state governments, increases the size of the Supreme Court (to 15), and replaces the Constitution—all to eliminate “red tape,” and create a functioning government.

At first, the White House staff is hesitant to follow (thinking he’s become insane), but one by one they conclude that it’s “a divine madness, the kind of madness that this crumbling world needs.”

Cover of Gabriel Over the White House, as published in Britain by Fantasy Books. Kemsley House, London. This is the version I read, but it was first published in Britain as Rinehard.

Cover of Gabriel Over the White House, as published in America by Farrar & Rinehart. Thomas F. Tweed’s name is not mentioned in the printed American version.

Oddly, the 1933 film credits list the Gabriel Over the White House author as “Anonymous.” Did Hollywood want to keep it hushed up that the author of “A Sensational Novel of the Presidency” was British? The story is told in first person by Hartley Beekman, Secretary to the President.

Tweed (1891-1940) was a British WWI Lieutenant-Colonel, and a political advisor to David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister.

According to Wikipedia, some characters in the novel are based on real people that both Tweed and Lloyd George knew.

Rinehard is set in the near future, and is about the world being given the government it “needs”—an efficient, benevolent dictatorship, where evildoers are punished.

(The secondary plot is a tale of Rinehard battling vicious Italian gangsters.)

Tweed later wrote another book known alternately as Blind Mouths or Destiny’s Man—which again involved a dictatorship and a healer.

It’s easy to figure out that Tweed was a Brit who never “crossed the pond.”

His novel is filled with British terms (“queue” instead of “line,” and “hire-purchase” instead of “buying on time”) plus awkward attempts at American slang.

(His gangsters seem based on British penny dreadfuls.)

A group of Chicago gangsters—"talking rapidly in Italian,” and described as “fat, swarthy, and soft-voiced”—are comically named Wolf Miller, Jose Borelli, “Spike” Jameson, and “Roddy” Greenblatt.

They commit a robbery with one thief costumed as Pierrot.*

(It’s strange that Tweed imagined that an Italian-American gangster would dress as an Italian clown; this “flourish” must have come from reading penny dreadfuls.)

The book was written in the 30’s, so it’s riddled with casual anti-Semitism, anti-Black, anti-immigrant and anti-Feminist sentiments.

A Chicago newspaper (Chicago Searchlight) is called a “filthy tabloid loved by Negroes, Jews and Italians.”

The President’s mistress/secretary (Pendie Malloy) is described as having a “faint strain of Jewish blood” because of her “acquisitive nose” and “full red lips.”

(“Acquisitive” is not my typo; that’s what Tweed wrote!)

The only sections that deal honestly with human emotions occur late in the novel, when an assassination attempt causes a head injury, and Rinehard returns to his former self.

Four years have passed since the car crash, but the befuddled Rinehard thinks it’s just days later.

He’s horrified to discover all the undemocratic measures he’s taken during his presidency, and wants none of it.

He asks that the White House staff set up the “television apparatus,” so that he may apologize to the nation.

However, his aides have become too invested in his legacy.

They refuse his request, causing a heart attack.

Rather than give Rinehard the medicine he needs, a staffer allows him to die.

The President’s legacy is left intact.

President Hammond (Walter Huston) and Pendola Malloy (Karen Morley). In the novel, the secretary’s name is “Pendie Malloy” (short for “Independence”), but in the movie her name is Pendola Molloy.

In the novel, the only indication that Rinehart is possessed by an Angel is found on page 64.

Pendie Malloy tells the narrator (Hartley Beekmann) that: “Sometimes when Rinehard is dictating, he seems to be at a loss at a certain point. . .He lifts his head and bends it sideways, for all the world as if he were listening to something or someone.”

Malloy speculates to Beekmann that “God has become a little merciful,” and has “sent Gabriel to do for Rinehard what He did for Daniel,” lead The Prophet in the right direction.

Tweed’s 1933 novel presents an America in which “people had lost all hope and faith and belief in their institutions,” and have “a deep distrust of politics.”

Above all, they need a “Leader.”

After President Reinhard begins to present his “Rinehart bedtime stories” on television, the populace dutifully lines up behind him.

There’s no need to gag the press, or to interfere in the free expression of public opinion.

(Indeed, a science fiction-fantasy! Rinehart’s “bedtime stories” preceded FDR’s fireside chats.)

Crime boss Nick Diamond in center (C. Henry Gordon) faces the President’s top aide, Hartley Beekman (Franchot Tone), on right. In the movie (and book), the President’s top aide heads a Federal Police unit that punishes criminals, not by imprisoning them, but with courts martial and firing squads.

The Hollywood film is somewhat different from the Tweed novel.

The film is set in the present (1933), rather than the late 1940’s.

The President’s relationship with his young secretary is obviously amorous in the film (but not so clear in the novel).

The film gangsters are slightly more realistic, and more “upscale.”

Several characters from the novel are combined in the film script, to simplify the plot.

The ending for the film is different too, with President Hammond dying after he’s signed a World Peace covenant.

However, the gist of the story is there.

Both the film, and the novel, are based on imagining whether America (and Britain too?) might be better off, if democracy was suspended and a “benevolent” dictator took power.

In Eleanor Roosevelt’s 1939 article “Keepers of Democracy” (in the Virginia Quarterly Review, Winter), she describes a world in which the people of the U.S. had allowed themselves “to be fed on propaganda which has created a fear complex. . . People have reached a point where anything which will save them from Communism is a godsend, and if Fascism or Nazism promises more security than our own Democracy, we may even turn to them.”

(Sadly, this description of propaganda-believers sounds very similar to what’s occurring in 2023.)

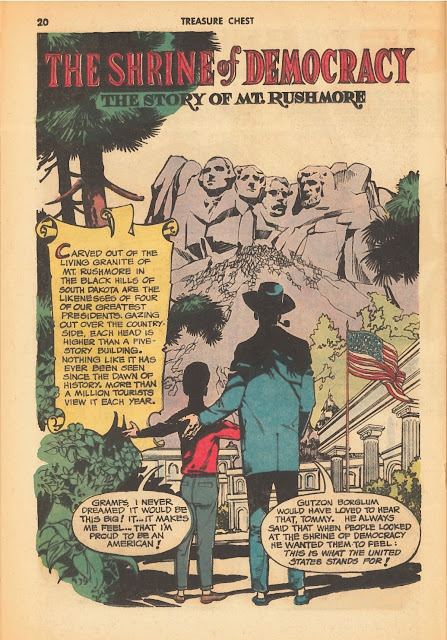

President Hammond (Walter Houston) addresses the “army of the unemployed” under a statue of George Washington and offers them jobs as the “army of construction.”

In Gabriel in the White House, President Hammond becomes a dictator, but he’s also a protective figure, who gives people a sense of security.

In the film, he walks—unescorted and Jesus-like—to address the “army of the unemployed.”

He bravely confronts the evil crime boss Nick Diamond in The Oval Office.

He’s aware of his role as a servant of God and Country, and becomes remote from human affections.

In 1933, President Hammond was the only type of benevolent dictator that Hollywood (and Hearst?) could imagine as a substitute for Democracy.

*”Pierrot” and “Harlequin” are both commedia dell’arte characters. In her youth, Dorothy L. Sayers did admit to enjoying trashy over-the-top “penny dreadfuls.” Their influence can be felt in Sayer’s 1933 Lord Peter Whimsey mystery, Murder Must Advertise. In that story, Lord Peter disguises himself in a Harlequin costume, while infiltrating a cocaine party, to solve a murder.